In 2024, the internet underwent a fundamental phase transition where the human web of chaotic, inefficient communication was largely subsumed by a layer of statistically optimized synthetic text. As Large Language Models like GPT-4, Claude 3.5, and Gemini achieve native-level fluency, we face an epistemological crisis where the provenance of the written word is no longer verifiable through simple observation. For engineers and data scientists, this situation presents a signal-to-noise problem rather than a moral panic about academic integrity. Generative AI is capable of immense utility, but when it masquerades as human insight, it introduces a specific type of low-entropy distortion that erodes critical thinking.

This post serves as a forensic analysis of the algorithmic fingerprint left behind by these models. We will move beyond superficial checklists of forbidden words to examine the probabilistic physics of Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) and next-token prediction architectures that compel these models to write with their distinctive, flattened cadence.

The physics of the stochastic parrot

To accurately identify synthetic text, one must understand the generative mechanism that produces it. Large Language Models operate as probabilistic engines designed to minimize perplexity, which in information theory is a measurement of uncertainty. A model with low perplexity is rarely surprised by the next word in a sequence because it consistently chooses the most statistically probable path. This results in a regression to the mean of human expression where the output is grammatically safe, structurally sound, and almost entirely devoid of the entropic spikes that characterize authentic human thought.

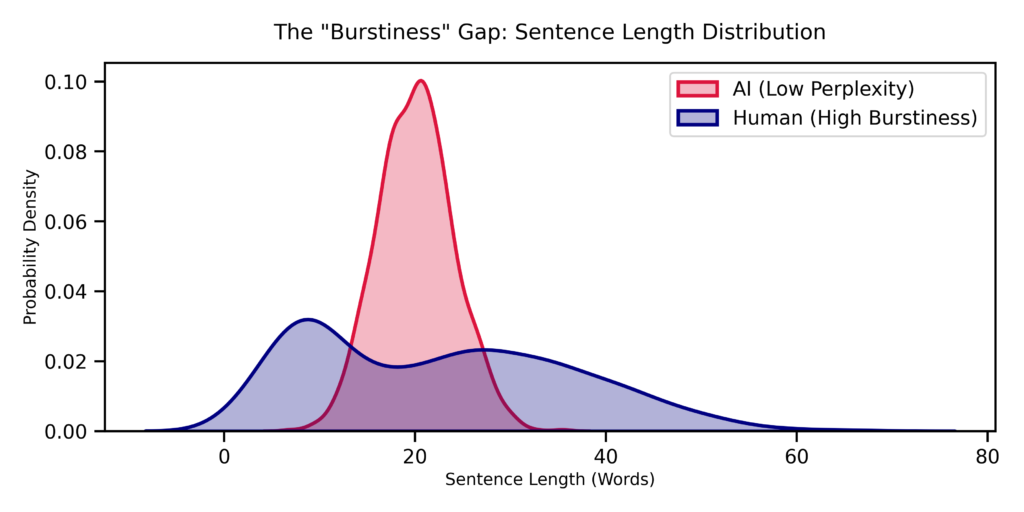

This distinction leads to the metric of burstiness, which measures the variance in sentence structure over the course of a document [1]. Humans are entropic agents who communicate in bursts, often following a labyrinthine sentence full of complex clauses with a short, punchy declaration to control the pacing of the narrative. The machine, by contrast, seeks a steady state and avoids sentence fragments or run-on sentences because they are statistically risky.

To visualize this distinction, I modeled the sentence length distributions of both human and artificial writers using a Python simulation. I represented the AI writing style as a tight Gaussian distribution centered around a safe average of twenty words per sentence, creating a homogenous curve that reflects its optimized safety. For the human distribution, I utilized a bimodal model with a heavy tail to capture our tendency to oscillate between extremely short interjections and long, complex theoretical explanations.

The resulting visualization reveals a stark disparity. As shown in Figure 1, the AI distribution appears as a narrow, peaked curve (in red) that hovers safely in the middle range. In contrast, the human signal (in blue) is messy and spreads into the ‘tails’ of the graph. If a text reads like a monotonous drone of perfectly average sentences, you are observing a system with low burstiness that is generating code rather than cognition.

The RLHF artifacts and feature engineering

The most recognizable linguistic markers of AI writing are not accidents but rather features of Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback. Research by Juzek and Ward tracked the explosion of specific words in scientific abstracts after 2022 and found that vocabulary usage is directly correlated with the reward models used during fine-tuning [2]. During this phase, human raters overwhelmingly prefer answers that sound neutral and comprehensive, which leads the model to optimize for specific words that sound sophisticated without being obscure.

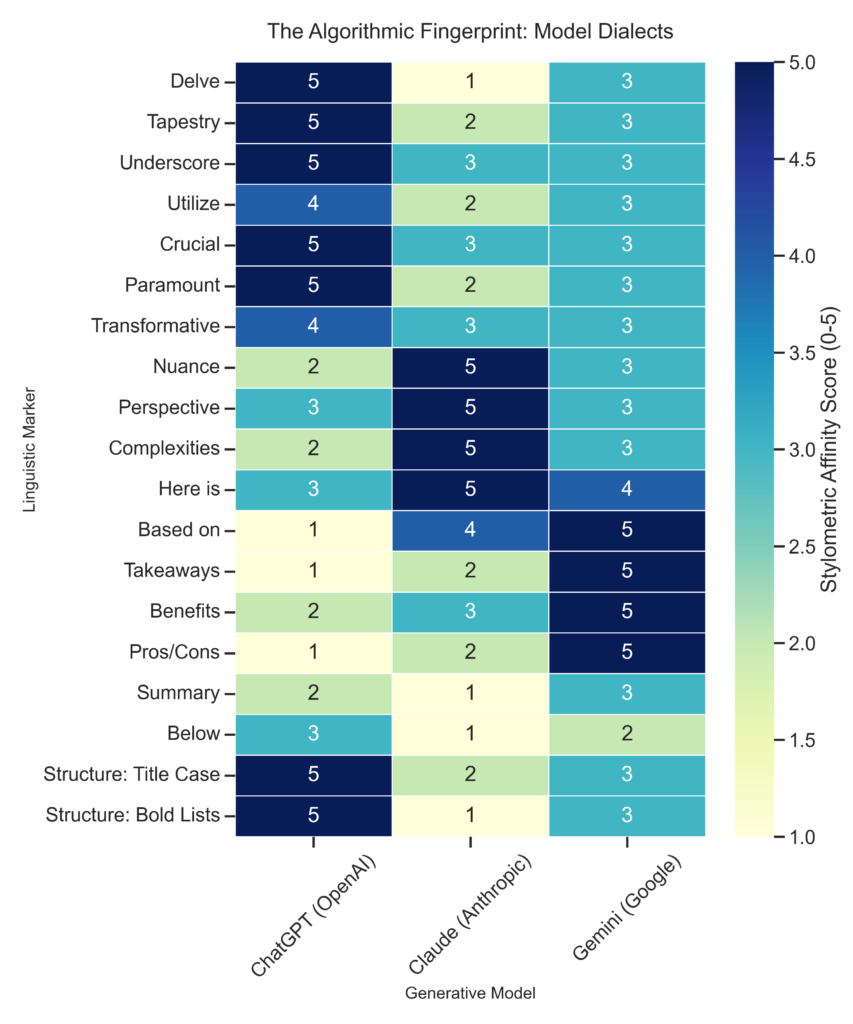

This optimization process creates distinct dialects for each model family. OpenAI’s ChatGPT frequently employs words that sound like an academic consultant, such as “delve,” “underscore,” and “paramount,” while Anthropic’s Claude often adopts a verbose and deferential tone using words like “nuance” and “perspective.” Google’s Gemini distinctively leans towards search-engine optimized structures filled with “key takeaways” and pros-and-cons lists [3].

Below figure shows these localized dialects and highlights how specific models have overfitted to their respective safety guidelines. Note the distinct vertical clusters: ChatGPT (left column) heavily favors authoritative connectors like ‘Paramount’ and ‘Crucial,’ while Claude (center column) is the primary offender for ‘Nuance’ and ‘Complexities.’ Gemini (right column) displays a unique structural fingerprint, strongly favoring ‘Based on’ statements and bolded lists.

The lexical blacklist and semantic voids

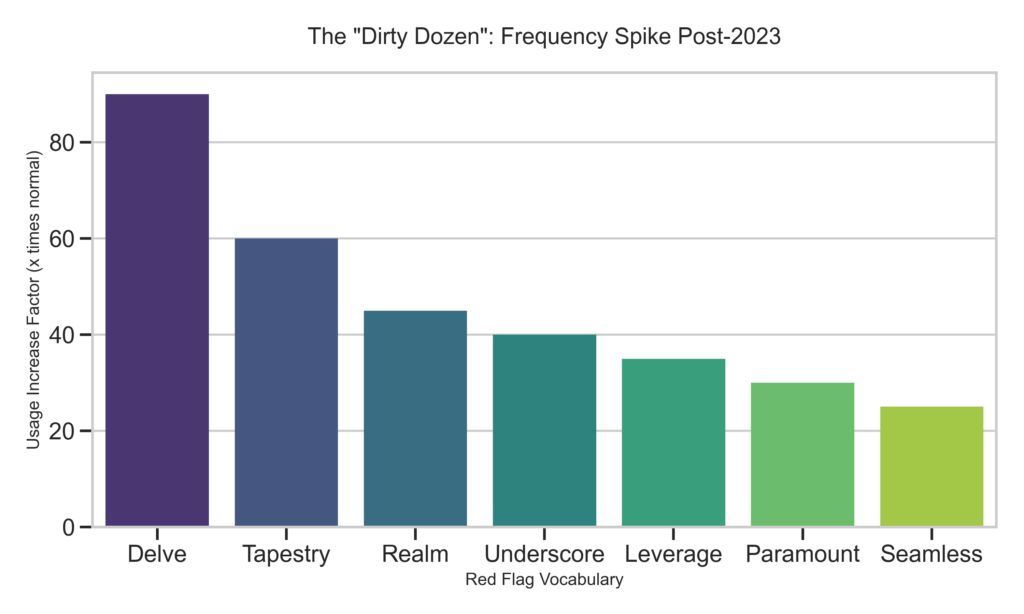

Forensic analysis reveals a specific set of vocabulary that has become statistically overrepresented in synthetic text. Words such as “delve,” “tapestry,” “landscape,” and “robust” appear with a frequency that defies natural language patterns. A human writer might use “dig into” or “examine” to describe an investigation, but the model has learned that “delve” yields a higher reward from its training function. Similarly, the machine frequently relies on “tapestry” to describe complexity because it is a safe literary flourish that connects disparate elements without requiring a specific analysis of their relationship.

As Figure above shows, this is not a subtle shift. The usage of ‘Delve’ and ‘Tapestry’ represents a vertical asymptotic spike in frequency. When a writer uses these terms, they are often unknowingly triggering a high-probability token selected by the model’s RLHF safety layer, rather than making a stylistic choice. Beyond individual words lies the problem of the semantic void, where the text is grammatically perfect but informationally empty. An AI might write that a robust solution facilitates a seamless transformation, which conveys zero bits of actual information. A human engineer would conversely state that the script reduced latency by forty percent. This lack of specific density is often the most damning evidence of artificial authorship.

The false positive paradox

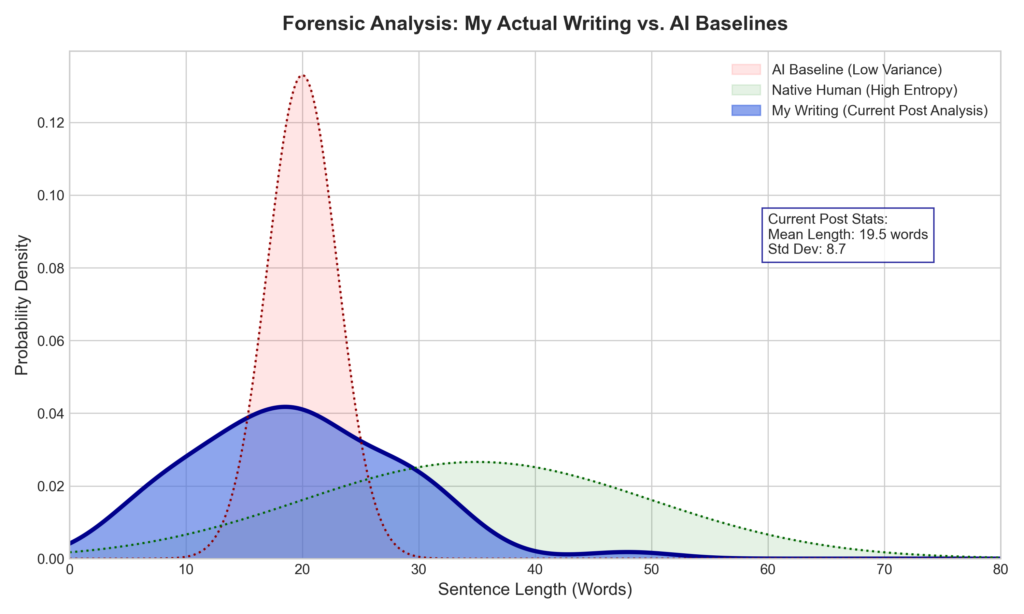

Current AI detection methodologies are significantly biased against non-native English speakers. Research from Stanford University revealed that detectors flag non-native writing as artificial up to ninety-seven percent of the time [4]. This occurs because non-native speakers often write with low perplexity, using standard textbook grammar and avoiding complex idioms to ensure clarity. To a detector looking for high burstiness and entropic phrasing, a careful ESL writer appears statistically identical to a safety-optimized GPT-4. Accusing a colleague or student based solely on a high probability score from a commercial scanner is therefore indistinguishable from statistical malpractice.

To demonstrate this, I analyzed the sentence length distribution of my current post (this very article). While I wrote this piece myself, I utilized slight AI assistance for editorial polishing. This hybrid context creates a perfect forensic test case. As a non-native English speaker, my writing style (Blue Line) prioritizes grammatical precision and clarity. The analysis reveals a mean sentence length of 19.5 words, which is strikingly close to the AI baseline (Red Line). However, my standard deviation is 8.7, significantly higher than the machine’s tight variance. This “False Positive” zone demonstrates how human intent—even when polished by algorithms—creates a statistical signature that commercial detectors frequently mistake for fully synthetic content.

Conclusion

The only reliable proof of humanity in the modern era is inefficiency. Artificial intelligence is optimized, clean, and seamless. Humans are messy, opinionated, and prone to structural choices that defy standard style guides. We write with a specific and idiosyncratic voice that cannot be averaged out by a loss function. The future of writing will not be defined by perfect grammar but by the presence of a high-entropy signal that no machine can currently simulate.

References

[1] Originality.ai. (2025). “Perplexity and Burstiness in Writing.”

[2] Juzek, T. S., & Ward, Z. B. (2024). “Why Does ChatGPT ‘Delve’ So Much?” arXiv.

[3] Comparative Model Evaluations, Detecting AI Writing Red Flags Dataset (2025).

[4] Liang, W., et al. (2023). “GPT detectors are biased against non-native English writers.” Patterns.

Disclaimer

This content is based solely on publicly available information.This content is for educational and entertainment purposes only. The author is not a financial advisor, and the content within does not constitute financial advice. All investment strategies and financial decisions involve risk. Readers should conduct their own research or consult a certified financial professional before making any financial decisions.

The opinions expressed in this article are my own and do not represent the views of Google.

Leave a Reply