It’s easy to think of your home stock market as a kind of mirror for the country’s economy—when things are going well, the market goes up, and if the currency gets stronger, your investments should be worth more around the world. That logic works pretty well in the US, where the S&P 500 and the Dollar tend to move together, but in the UK, this connection can be misleading and even risky if you take it at face value.

If you’re investing in the UK, it’s important to notice that the FTSE 100 doesn’t always reflect what’s actually happening in the British economy you see every day. This isn’t just about how people feel or what the headlines say—it’s built into the way the index works, and if you don’t spot it, you might find your portfolio quietly losing ground when it comes to buying power around the world.

We observed this mechanism in its most violent form on June 24, 2016. As the results of the Brexit referendum became clear, the British Pound collapsed, falling over 8% against the US Dollar in a single day. Logic dictates that a country voting to leave its largest trading bloc should see its stock market plummet. Yet, the FTSE 100 did not crash. It finished the week higher.

This strange pattern actually points to the heart of how the UK market works: when you buy the FTSE 100, you’re not really betting on Britain itself—you’re betting against the Pound. Let me explain it why in this post.

The faded empire and the currency slide

To see why the FTSE 100 and the Pound often move in opposite directions, it helps to start with the currency itself. The British Pound has spent the last hundred years slowly slipping from its spot at the top of the world to something much more ordinary.

Until 1914, Pound was the world’s undisputed reserve currency. The gold sovereign was convertible anywhere, and London was the clearinghouse for global trade. World War I broke this dominance. The immense cost of the conflict forced Britain to liquidate its overseas investments and borrow heavily from the United States. By 1920, the mantle had begun to slip, though the Pound fought to maintain parity with gold.

The death knell for Pound’s supremacy came in 1944 at Bretton Woods, where the US Dollar was anointed the anchor of the new global monetary system. Britain, effectively bankrupt after fighting a second total war in 30 years, could no longer support the currency’s value. The post-war years were marked by humiliating devaluations, culminating in the 1956 Suez Crisis. When the United States threatened to sell its Pound bond holdings to force a British withdrawal from Egypt, the fragility of the Pound was exposed to the world. A 14% devaluation followed in 1967.

By the time the 1970s rolled around, the Pound had already lost its place as a top reserve currency, shrinking from nearly a third of global reserves to just a fraction. These days, it’s less than 5%. For anyone investing in the UK, this long, slow slide matters a lot, because if you only hold assets priced in Pounds and don’t have a way to tap into value created abroad, you’re basically betting on a currency that’s been getting weaker for generations.

A tale of two indices

The London Stock Exchange eventually created two main indices, and over time, these have come to stand for two very different sides of the UK economy.

The FTSE 100, which people often call the ‘Footsie,’ started in 1984 with 1,000 points on the board, and it was meant to track the biggest 100 companies in the UK. Right from the start, it was packed with the kinds of businesses that shaped the last century—think oil, mining, tobacco, and banks. Over time, it turned into a sort of global resource machine, full of huge companies that are based in London but actually make most of their money in other parts of the world.

Then, in 1992, the FTSE 250 came along to track the next 250 biggest companies, which are usually called mid-caps. Unlike the Footsie, the FTSE 250 is filled with housebuilders, shops, local banks, and service companies, so it actually gives you a much better sense of how the UK economy itself is doing.

So now we have this interesting split: the FTSE 100 is all about global earnings and looks outward, while the FTSE 250 is much more focused on what’s happening at home, giving you a window into the health of UK consumers and businesses.

The mechanics of the decoupling

The reason the FTSE 100 and the Pound often move in opposite directions comes down to something pretty straightforward: most of the money these big companies make—about three-quarters or more—actually comes from outside the UK.

Take a company like Rio Tinto or Shell—they sell things like iron ore and oil in US Dollars, and their costs are spread all over the world, but their shares are priced in Pence. So, when the Pound drops against the Dollar, every $100 they make from a barrel of oil suddenly turns into more Pounds on their books.

For example, if the exchange rate is 1.50, then $100 in profit is worth £66, but if the Pound falls to 1.20, that same $100 suddenly becomes £83. The company hasn’t actually sold more oil or become more efficient, but just because of the weaker Pound, their reported earnings in Pound jump by a quarter, and the share price usually moves up to match.

This is what people mean when they talk about the ‘Decoupling Effect’—bad news for the UK economy can actually make the Pound weaker, but that often ends up making the FTSE 100 stronger.

The FTSE 250 works the other way around, since about half of its revenue comes from inside the UK. When the Pound gets weaker, it’s almost like these companies are hit with an extra tax on anything they import. So, if a British retailer is buying products from China or Europe, those goods get more expensive, and at the same time, shoppers in the UK start to feel the pinch and spend less. All of this puts pressure on the profits and sales of FTSE 250 companies.

Analyzing the correlation

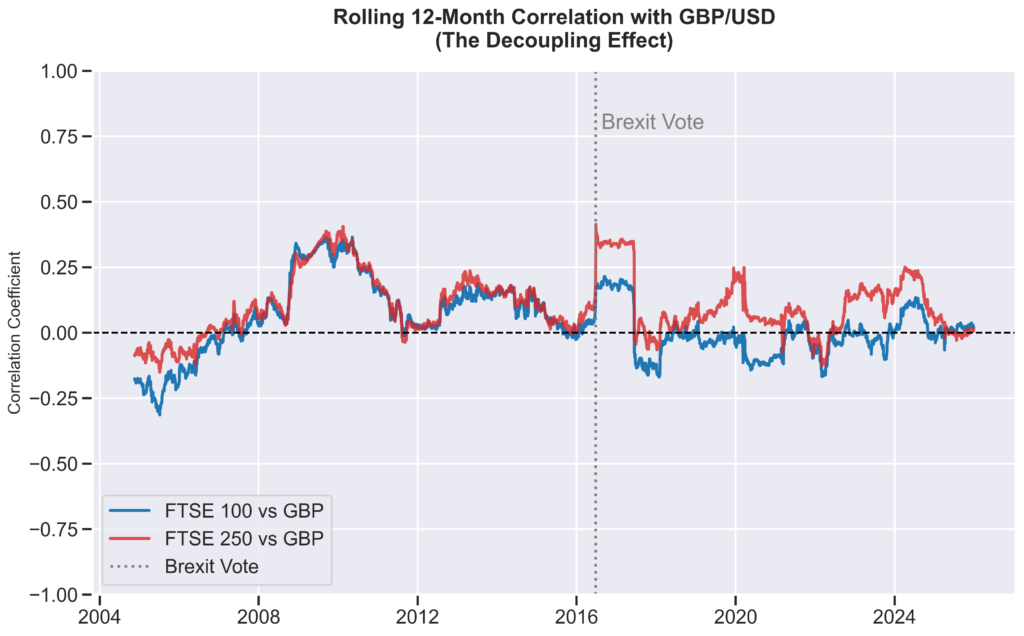

We ran a Python analysis to quantify this relationship, calculating the rolling 12-month correlation between the indices and the GBP/USD exchange rate over the last decade. The data confirms the structural split as you can see in below figure:

If you look at the last decade, the average connection between the FTSE 100 and the Pound-Dollar exchange rate is basically zero, but that doesn’t tell the whole story. In times when the Pound is under real pressure—like after the Brexit vote in 2016—the link turns strongly negative, which means the FTSE 100 tends to go up when the Pound drops.

On the other hand, the FTSE 250 usually moves more in line with the Pound, with a positive correlation that sometimes gets quite strong. Even though the numbers aren’t huge—markets are always a bit messy—the real takeaway is that the FTSE 100 and FTSE 250 respond very differently when the Pound moves.

The “low to zero” correlation of the FTSE 100 is effectively a hedge. It tells us that holding the FTSE 100 neutralizes the currency risk of the Pound. It is a natural dampener. The FTSE 250, with its positive skew, amplifies the domestic economic signal.

The opportunity cost (Total Return)

Even though this decoupling gives you a smart way to hedge your portfolio, it hasn’t come for free. If you look back over the last 30 years and compare the total returns—including dividends—of the FTSE indices to the S&P 500, the difference is hard to miss:

The S&P 500 has turned into a real engine for building wealth, mostly thanks to the huge growth in tech companies. The FTSE 100, by comparison, has acted more like a high-yield bond, with slow growth in share prices and most of the returns coming from dividends.

If you’re a UK investor, this really shows the cost of sticking too closely to home. By putting too much into the FTSE 100 just to protect against currency swings, you might have missed out on the rapid growth of US tech and ended up with the slower, steadier returns of traditional big companies.

Under the hood: The Granite 11

If you want to understand why the FTSE 100 behaves the way it does, it helps to take a closer look at what’s inside. While the S&P 500 gets most of its energy from a small group of fast-growing tech companies that people call the ‘Magnificent 7,’ the FTSE 100 has its own set of big players, but these are more about reliability and endurance than excitement, so I like to think of them as the ‘Granite 11.’

Roughly a third to nearly half of the FTSE 100 is made up of just a dozen really large companies, and these ‘Granite 11’ tend to steer the whole index, even if the other companies are moving in different directions. By early 2026, these are Granite 11:

- AstraZeneca & GSK: The pharmaceutical fortress.

- Shell & BP: The energy supermajors.

- HSBC & Barclays: The global banking giants.

- Rio Tinto & Glencore: The resource miners.

- Unilever, Diageo, & BAT: The consumer defensive staples.

When you look at this list, you’ll notice there isn’t any tech in sight—no artificial intelligence, no cloud computing, and no semiconductor companies. Instead, it’s all about resources, energy, healthcare, and banks, which can make the FTSE 100 seem a bit dull when technology stocks are taking off, but that same mix can actually help protect you when inflation is high.

The list of companies in the index doesn’t just sit still; instead, it gets a regular shake-up, which people call the ‘Quarterly Reshuffle.’ Four times a year—in March, June, September, and December—the folks at FTSE Russell look at each company’s size in the market and update the list, making sure the biggest players stay in while some of the smaller ones might get swapped out. There’s a kind of invisible line at the 90th spot, and if a company from the FTSE 250 grows big enough to cross it, that company gets bumped up into the FTSE 100 automatically. But if one of the big companies slips down to the 111th spot or lower, it doesn’t get to stay in the FTSE 100; instead, it moves down into the mid-cap group.

This whole system keeps the index centered on the biggest companies, although it does mean there’s a bit of a lag, because companies usually get promoted after their share prices have already gone up and get dropped after they’ve already taken a hit.

In contrast to the top-heavy nature of the big index, the FTSE 250 looks much more like a diverse ecosystem where no single company is allowed to dominate the landscape. While the FTSE 100 is heavily concentrated in just a few massive sectors, the mid-cap index is actually famous for its huge collection of Investment Trusts, a sector that accounts for nearly a third of the entire index. This group includes dozens of different funds—such as 3i Infrastructure or Polar Capital—which means that when you buy the FTSE 250, you aren’t just buying individual operating businesses but you are also gaining exposure to a wide variety of managed portfolios that invest in everything from private equity and renewable energy to technology stocks in Asia.

The other thing you will notice is that there is no “Granite 11” equivalent here because the index is much flatter and far less concentrated at the top where the largest company rarely makes up more than 1% of the total index. Instead of relying on a few titans to carry the load, the FTSE 250 behaves more like a swarm of medium-sized businesses that includes recognizable household names like British Land which owns huge chunks of London property, major housebuilders like Bellway that rise and fall with the local housing market, or insurance giants like Hiscox and bakery chains like Greggs which are all pulling in the same direction based on the health of the British economy.

Strategic implications for the portfolio

When you start to see that the FTSE 100 and FTSE 250 each move in their own way, it gets a lot simpler to put together a portfolio that actually fits how you feel about the UK, and you can do this without worrying that you’re secretly making a huge bet on what the Pound will do next.

If you’re not feeling too confident about the UK economy or the Pound—maybe because of things like high debt or sticky inflation—the FTSE 100 can actually be a way to give yourself some protection. When you invest in it, you’re really getting a slice of big global companies like Shell, AstraZeneca, and HSBC, so you end up sharing in their growth and earnings from all over the world, often in dollars, and you don’t even have to mess around with opening an account overseas. It’s almost like you’re hedging your bets against the Pound, but you’re still doing it through the UK stock market you already know.

If you’re looking for a way to bet on the UK making a comeback, the FTSE 250 is probably the best place to start, since it’s packed with companies that are closely tied to the British economy. When things pick up in the UK, the Pound usually gets stronger, which makes it cheaper for these mid-sized businesses to buy what they need from abroad and can also make shoppers feel a bit more confident. Over the long run, the FTSE 250 has tended to do better than the FTSE 100 because it’s more exposed to this kind of homegrown growth, although it’s worth keeping in mind that it can swing around a lot more and is more affected by whatever’s happening in UK politics.

It is also worth checking under the hood of your developed market ETFs because they don’t all give you the same slice of Britain. If you hold standard “international” funds like the iShares MSCI EAFE ETF (EFA) in the US or the BMO MSCI EAFE Index ETF (ZEA) in Canada, you are tracking the standard MSCI EAFE Index. This index only buys the largest 85 or so companies in the UK, which means your exposure is effectively just the FTSE 100 minus a few smaller players. In this scenario, you are getting all the global currency hedging and dividend giants, but you are missing out on the deeper domestic economy found in the FTSE 250.

On the other hand, if you hold the “Core” or “IMI” versions—specifically the iShares Core MSCI EAFE ETF (IEFA) in the US or the iShares Core MSCI EAFE IMI Index ETF (XEF) in Canada—you are tracking the much broader MSCI EAFE IMI (Investable Market Index). These funds hold nearly 270 UK companies, which is a crucial difference because they don’t just stop at the “Granite 11” and their global peers. Instead, they dig deeper to include hundreds of mid-sized housebuilders, local banks, and retailers, giving you a fighting chance to capture the local British economic recovery that the standard funds leave behind.\

Conclusion

It’s tempting to just buy a tracker fund that follows the main UK index and call it a day, but as we’ve seen, picking the FTSE 100 doesn’t really mean you’re investing in the UK itself—you’re actually buying into a bunch of global companies that just happen to report their results in Pounds.

To put together a strong portfolio, it’s important to separate these two types of risk. The FTSE 100 can help you collect global dividends and protect yourself from a falling Pound, while the FTSE 250 lets you focus on UK growth when the timing looks right. Just remember—they’re not the same thing, and they don’t move together.

The Pound might never get back to its glory days, but if we understand how these indices work, we can make sure our portfolios don’t end up following the same downward path.

References

- FTSE Russell. (2024). FTSE UK Index Series: Monthly Review. London Stock Exchange Group.

- FTSE Russell. (2024). Ground Rules for the Management of the FTSE UK Index Series. London Stock Exchange Group.

- Bank of England. (2024). Sterling Effective Exchange Rate Index. Bank of England Statistics.

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2024). UK Trade: Goods and Services Publication.

Disclaimer

- The opinions expressed in this article are my own and do not represent the views of Google.

- This content is based solely on publicly available information.This content is for educational and entertainment purposes only. The author is not a financial advisor, and the content within does not constitute financial advice. All investment strategies and financial decisions involve risk. Readers should conduct their own research or consult a certified financial professional before making any financial decisions.

Leave a Reply