For as long as people have been trying to build a business in space, gravity has been the main thing everyone has to work around, since it takes a huge amount of energy—and money—to get anything off the ground. But as we get closer to 2026, it feels like there’s a new factor taking over the conversation, and that’s monopoly.

There’s so much chatter right now about what’s next for the space industry, especially with all the talk about a possible SpaceX IPO and that eye-popping $1.5 trillion valuation. It’s easy to feel like the whole market is just about finding a way to get in on something that seems set up for Elon Musk to win. But if you look past the headlines, you can see a split forming: on one side, there’s this giant, vertically integrated company that almost feels like its own country, and on the other, there’s a bunch of smaller players all trying to carve out a spot for themselves—whether that’s in spectrum, launch contracts, or just a piece of orbital real estate. Speaking as someone who thinks like an engineer, I’ve never been convinced by those dramatic growth charts; I’d rather look at what the physics and the cash flows are telling us. Right now, both of those are changing in ways that most everyday investors probably haven’t noticed yet.

The $1.5 trillion gorilla

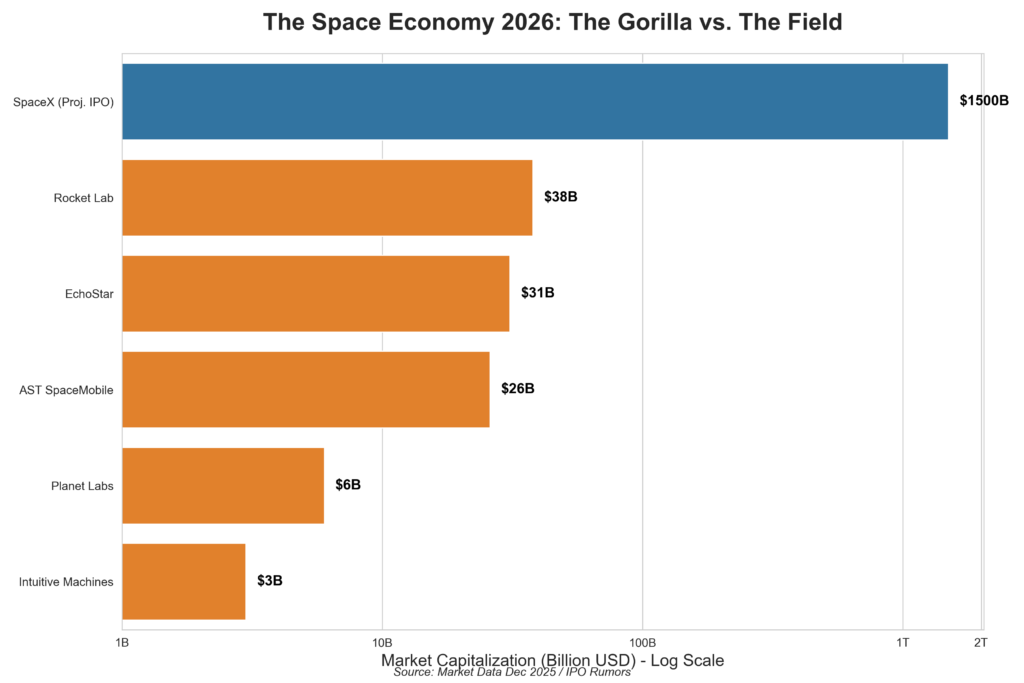

Let’s start with the obvious question everyone is asking. Most signs now point to SpaceX aiming for a public offering sometime in the second half of 2026, and if the rumored $1.5 trillion valuation is anywhere close to reality, that would make it worth more than just about every traditional aerospace company put together. Does that number actually make sense? If you look at it through the usual lens of price-to-earnings ratios, probably not. But SpaceX has shifted from just selling rockets to selling data, with Starlink bringing in so much revenue—over $22 billion, by some estimates—that it can help pay for the huge costs of building and launching Starship. When you see the gap in market value between SpaceX and everyone else, it’s not just big; it’s on a completely different scale.

If you’re not able to invest directly in private companies, EchoStar (SATS) has become an interesting, though risky, way to get indirect exposure. After selling off some valuable spectrum licenses to SpaceX in exchange for both cash and a big chunk of SpaceX stock, EchoStar now owns a significant piece of Musk’s company. So, owning SATS isn’t just about old-school satellite TV or 5G anymore—it’s more like holding a ticket that could pay off if and when SpaceX goes public at that huge valuation, since EchoStar’s balance sheet would benefit just by being along for the ride.

There’s also a new idea taking shape that might sound like something out of science fiction, but it actually comes from the basic rules of physics: building AI data centers in orbit. Here on Earth, data centers run into a big problem with heat. We use a lot of energy—often from fossil fuels—to power the computers, which then get hot, and then we have to spend even more energy to cool them back down. It’s a pretty inefficient cycle.

But in space, you get two big advantages for free: constant solar power, since there’s no atmosphere in the way, and the cold of deep space, which is just a few degrees above absolute zero. Some companies, like Starcloud and Aetherflux, are betting that putting powerful GPUs in orbit could let them run faster and stay cooler, which would make training AI models much cheaper. This isn’t just a thought experiment, either—Starcloud already launched a test version in 2025, so if this setup works in 2026, it could really change the economics of AI.

The “real” space stocks: A 2026 watchlist

If we think of SpaceX as the baseline for the whole sector, then the real opportunity might be in the companies that are building the tools and infrastructure everyone else needs to operate in space. The figure below shows SpaceX vs. its competitors. Now let’s analyze them one by one.

EchoStar (SATS)

If you’ve ever wished you could invest in private companies but found the door closed, EchoStar might be the most interesting workaround out there, even if it’s a bit complicated to untangle. EchoStar, which is now worth about $31 billion, has moved far beyond its old reputation as just a satellite company, because the real story is in the spectrum it owned—something that turned out to be exactly what Elon Musk and SpaceX needed. When EchoStar traded some of its valuable S-band spectrum licenses to SpaceX, they didn’t just walk away with cash; they also ended up with a meaningful stake in SpaceX itself, so the company has quietly shifted from being a straightforward satellite operator to more of a holding company with a foot in some very interesting doors. These days, owning SATS isn’t really about satellite TV or trying to guess where 5G is headed, since for a lot of people, it’s starting to feel more like a clever way to get a piece of SpaceX before it goes public, and maybe even at a bit of a discount.

That said, the numbers behind EchoStar aren’t exactly straightforward. While the $31 billion price tag hints at just how much people are banking on that SpaceX stake, there’s still the reality of EchoStar’s debt and the fact that its old DISH network business isn’t bringing in what it used to. So, what you’re really looking at is a bit of a waiting game: can EchoStar keep its finances steady long enough for the SpaceX IPO, which is expected in late 2026, to actually happen? If SpaceX does end up being valued at $1.5 trillion, then EchoStar’s share could, at least on paper, be worth more than the whole company is today—which would mean you’re basically getting everything else EchoStar does for free

Rocket Lab (RKLB)

People often call Rocket Lab the “second best” launch provider, but that really doesn’t do justice to what they’re building. With a $38 billion market cap, investors are clearly seeing more than just the Neutron rocket, even though the delay of Neutron until 2026 is a bit of a setback in their race with SpaceX. What’s easy to miss is that Rocket Lab has been quietly growing a huge “Space Systems” business, making things like solar panels, reaction wheels, and separation systems for other companies’ satellites. So, instead of just being the company that delivers payloads to space, they’re also the ones building the parts that make those missions possible—sort of like being both the trucking company and the mechanic’s shop.

This kind of diversification is really what sets Rocket Lab apart from other launch startups and helps explain why the market is willing to pay a premium for their stock. While they wait for the Neutron rocket to be ready, their smaller Electron rocket is still the only commercial launcher that’s proven itself reliable outside of SpaceX’s Falcon 9, which means they have a steady stream of cash coming in. The big hope for 2026 is that Rocket Lab can bring these two sides of the business together—if they can use Neutron to launch their own satellite constellations or offer ready-to-go satellites for customers, they’ll move from being just a service provider to more of a platform. So, at $38 billion, what investors are really betting on is that Peter Beck can pull off the same kind of vertical integration that made SpaceX a giant, just on a smaller scale.

AST SpaceMobile (ASTS)

AST SpaceMobile might be the biggest all-or-nothing story in this group. Their $26 billion valuation is really a bet on one big idea: making it possible for regular smartphones to connect directly to satellites, without any special hardware. The physics behind this is a huge challenge, since picking up a faint signal from a phone in someone’s pocket on Earth means the satellite needs an antenna array that’s not just big, but absolutely enormous—think bigger than most apartments. Designing, building, and launching these giant, foldable antennas takes a lot of money, and AST is spending heavily to get their “BlueWalker” satellites up and running before anyone else can catch up.

What really shapes the future for ASTS is who they’re working with and who they’re up against. While SpaceX has teamed up with T-Mobile, AST SpaceMobile is working with AT&T and Verizon, which has basically turned low-Earth orbit into a new battleground for the big telecom companies. If ASTS can show by 2026 that their software can handle millions of users connecting at once without causing interference, then that $26 billion price tag might actually look like a bargain, especially when you think about the steady income from global roaming fees. But if they run into technical problems with those huge antennas and can’t keep up the pace, there’s a real risk that investors won’t be willing to fund the next round of launches.

Planet Labs (PL)

Planet Labs might look small compared to some of the giants in the space industry, since their market cap is around $6 billion, but what they’re doing stands out because they focus less on building rockets and more on turning satellite data into something useful for people on the ground. They have a whole fleet of Dove satellites that circle the planet and take pictures of the entire Earth every day, and instead of trying to create a new internet in space, their real aim is to become the main place people go for Earth data. You can think of it like a Bloomberg Terminal, but instead of financial numbers, it’s satellite images that can help everyone from farmers checking on their crops to hedge funds tracking oil supplies or governments watching their borders.

One way to look at Planet is that they’ve already made it through the hardest part, since their whole network of satellites is up and running. The big question for them now is what happens as satellite images become easier and cheaper to get, because more companies are sending up their own high-tech cameras. What really sets Planet apart is their huge archive of images, which goes back for years and gives them a head start when it comes to using AI to spot patterns and changes over time. If they can shift from just selling pictures to actually offering insights based on all that data, they could end up being a steadier and less risky way to invest in the space industry than the companies focused on launching rockets.

Intuitive Machines (LUNR)

Intuitive Machines, valued at $3 billion, is the smallest player on this major watchlist, but it holds the keys to the most romanticized sector: the Moon. Unlike the Low Earth Orbit (LEO) economy, the lunar economy is still in its infancy, heavily subsidized by NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program. Their “Nova-C” landers are designed to deliver science experiments and cargo to the lunar surface. The valuation is currently capped because, frankly, landing on the Moon is statistically one of the hardest engineering feats humans attempt; high-profile failures by other nations and companies have kept inveLooking ahead to 2026, the story is starting to move away from just exploring the Moon and toward actually building things there. Intuitive Machines isn’t just hoping to deliver packages; they’re also going after contracts to set up communication relays and even build the Lunar Terrain Vehicle. If they manage to land the right government deals, they could become the main logistics company for NASA’s Artemis program. At $3 billion, owning the stock is a bit like making a leveraged bet on whether the US government will keep pushing for a permanent base on the Moon. If that support stays strong, Intuitive Machines could be the go-to contractor, but if the government loses interest, there really isn’t much of a commercial market for sending stuff to the lunar surface. is virtually non-existent.

The “boom and bust” warning

We’ve been through a version of this before. Back in 2020 and 2021, there was a wave of space companies going public through SPACs, but a lot of them were really just ideas on slides rather than real businesses. Most of those are now trading for pennies or have gone bankrupt, like Virgin Orbit and Astra. This new wave in 2026 feels a bit different, though, because the companies that are still standing—like Rocket Lab, Planet Labs, and Intuitive Machines—actually have working hardware in space and real revenue. Still, the basic challenge hasn’t changed: building anything in space takes billions of dollars up front, and it can take decades before you see a real payoff.

If you’re thinking about investing in this sector, it’s less about finding undervalued companies and more about believing that the economy in low-Earth orbit will grow as quickly as the internet did. It’s worth remembering, though, that even in 1999, when everyone agreed the internet was the next big thing, buying the wrong company—like Pets.com—still meant losing everything. So, it’s probably safest to focus on companies that actually have rockets ready to launch and enough money in the bank to keep going, because gravity always wins in the end.

Disclaimer

This content is based solely on publicly available information.This content is for educational and entertainment purposes only. The author is not a financial advisor, and the content within does not constitute financial advice. All investment strategies and financial decisions involve risk. Readers should conduct their own research or consult a certified financial professional before making any financial decisions.

The opinions expressed in this article are my own and do not represent the views of Google.

Leave a Reply